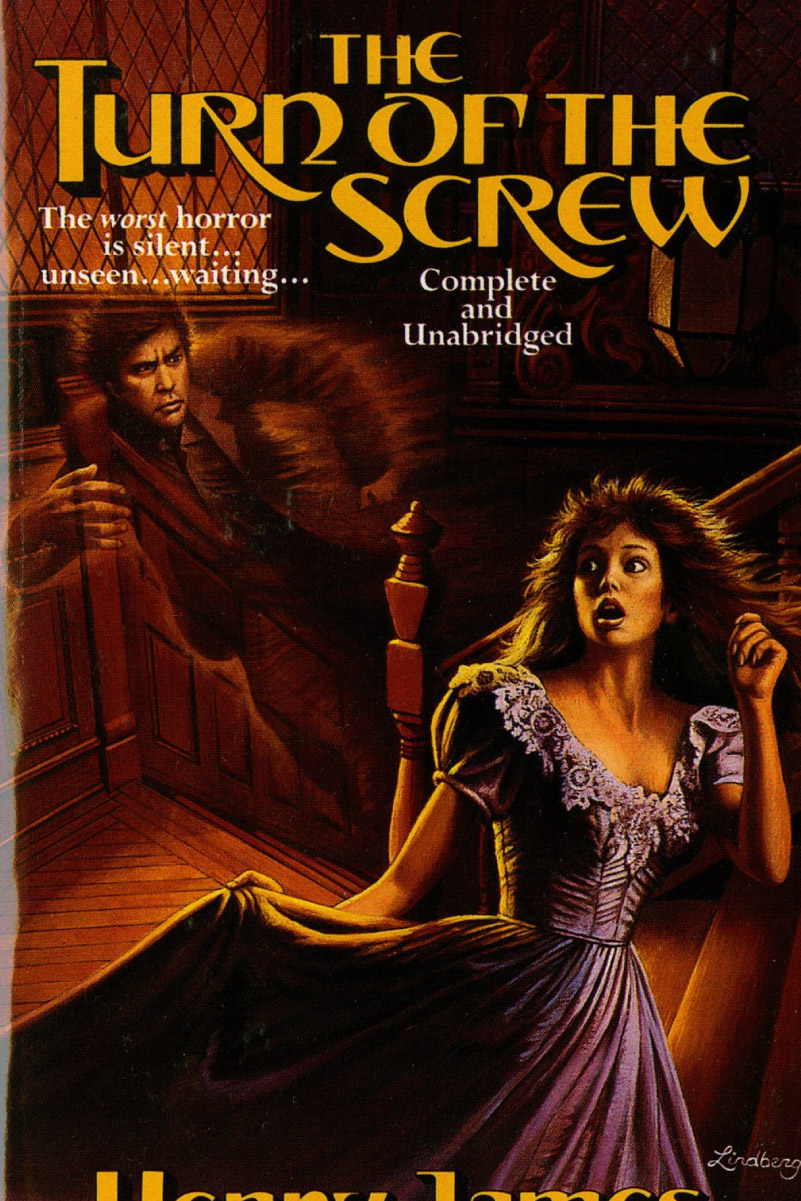

The Turn of the Screw

by Henry James

“I had the fancy of our being almost as lost as a handful of passengers on a great drifting ship” (15). “Well,” she says, “I was strangely at the helm!”

Henry James’ iconic novella, “Turn of the Screw,” analyzes the increasingly manic mind of a governess who is thrown into the spooky Bly Manor with two odd children and a morbid past. The two children have no parents, their uncle is off in England, and their past governess and the manor’s past valet have both died somewhat gruesome deaths and appear to haunt the place and its inhabitants. Throughout the book, the governess attempts to figure out if the ghosts are real, or if she is simply gone insane. She fears that if the ghosts are real, they are attempting to weaken her standing at Bly by making her appear crazed.

However, there are complications beyond just the haunting of the manor: the governess might have other plans for herself at Bly, beyond just teaching and taking care of the two strange children. She perhaps wants to take control of Bly, seduce the inattentive uncle, or murder the children. Her goals aren’t clear—and for a reason. The governess is the one writing her tale—as made clear in the prologue, where a man boasts about a ghost story more fearsome than any other at a dinner party and reads aloud the governess’s tale—and as Miles dies in her arms at the very end of the book, she can’t disclose her motives. The governess could be clinically insane, or just quite skillful in her attempts for power.

James takes pride in his verbiage, making slight etymological links that accentuate the novella. The names of all the characters, for instance, play a hilariously strong role in how they behave. Miles, the young boy, acts like an odd soldier, much like his name in Greek. Flora, the young girl, makes use of flora and fauna to plan her escape from Bly. Ms. Grose, the manager of the manor, is, as put, gross and unsightly. The governess, interestingly enough, isn’t given a proper name—to the readers, she maintains herself as simply, “the governess,” perhaps to show that her character is the most complex and confusing of them all (even more so than the ghosts, one might argue). Another instance of James’ etymological prowess is when Flora plays with twigs in the grass and figures “a mast” to “ make the thing a boat.” The usage of the word “mast” might have further meaning. Mast relates to the term “master.” A mast is also relatively stoic, standing still and at the center of the boat. This might have relevance to the fact that the ghosts don’t ever seem to move. They simply stand still and stare. Their stillness is what gives them power, by creating an air of ambiguity. This is another instance of the governess imagining that the ghosts are attempting to gain the role of master of Bly. The words that James chooses makes clear the governess’ anxiety about the other inhabitants of Bly.

A short albeit difficult read, the novella is an outstanding piece of work that analyzes the power of paranoia and the supernatural, not just through plot and dialogue, but also through stiff verbiage and etymologies.