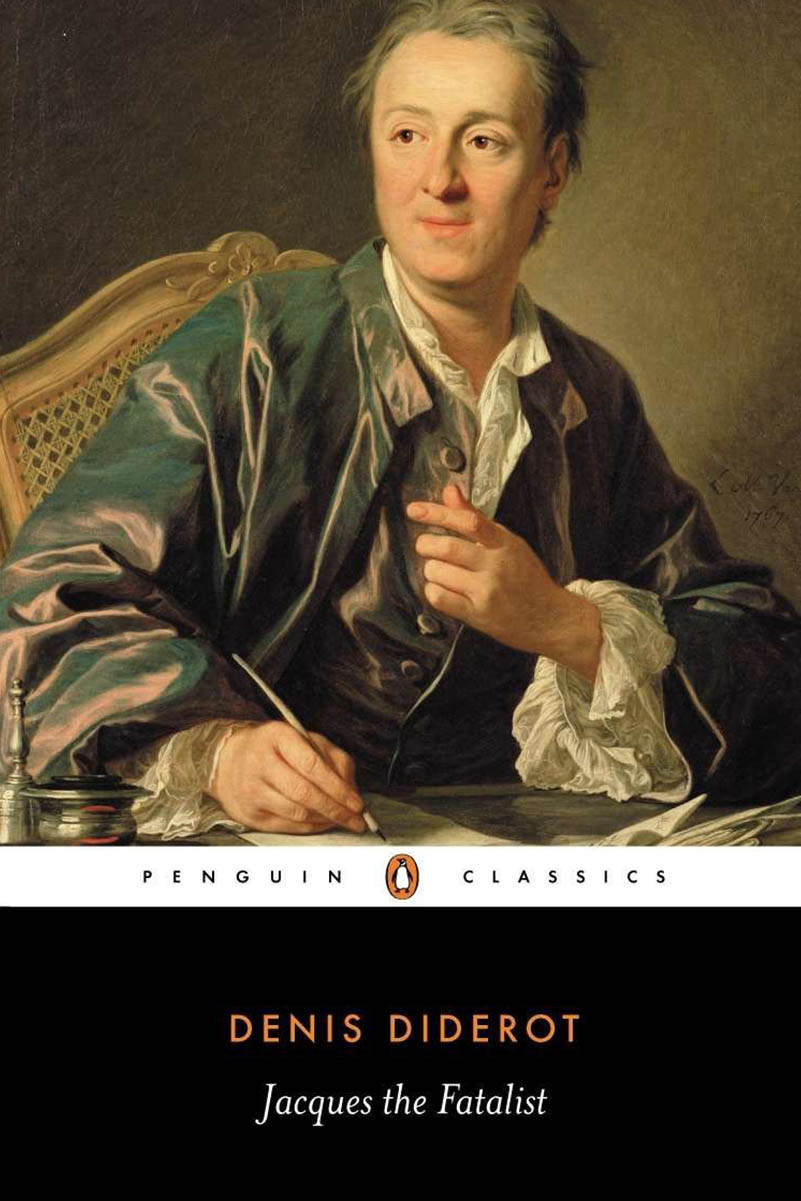

Jacques the Fatalist

by Denis Diderot

“Reader, you’re way off target. By trying too hard to be clever, you’re being very, very stupid.”

This quote perfectly encapsulates the informality and the comedic nuances of Denis Diderot’s Jacques the

Fatalist. Jacques the Fatalist is not a typical 18th century picaresque novel—it has a completely fresh take on the “adventure” novels of the time. Although it is advertised as Jacques telling his master a plethora of love stories while they travel together, it is anything but. Jacques the Fatalist interacts with the reader, is littered with non-sequiturs, and infiltrates a seemingly simple plot with philosophical musings.

As the name suggests, Jacques is a fatalist; he believes in fate—in that everything he is set to achieve in his life is already “written on high,” on a long scroll that unravels slowly. The novel’s fatalistic musings seem to imply that the reader should know what is coming next—as in many novels, the reader assumes the role of an overlooking god.

Yet, Diderot completely flips the script. Everything that occurs in his novel is unforeseeable to the reader and a complete surprise.

Diderot pushes the reader to change their views about the novel. That is, novels should not be flimsy, satisfying and comfortable love stories but rather reflect the complex, intricate and often unrewarding stories which confront real life. Jacques’s fascinating stories about his love life don’t come easy to the reader. The readers are forced to dig through the rubble to find the occasional paragraph about a brief tryst between a country girl and

Jacques. In such a way, the reader is given Diderot’s interpretation of life: life is not clean-cut and fluid.

The novel plays on the fact that it’s demographic are people who want only what they know: love stories. The book’s plot is advertised as a collection of Jacques’ love stories, yet the writer, seemingly wanting a reaction from his audience, has Jacques be interrupted so frequently that the story no longer stays on course. For example, early on in

Jacques the Fatalist, “a kind of country bumpkin […] spoke up” (5), interrupting the flow of Jacques conversation. The country bumpkin and a surgeon proceed to then have a long and rambling dispute with Jacques and his master—one that lasts several pages. The novel is littered with such interruptions, baiting the reader to lash out. The reader’s convenience in Jacques the Fatalist is hardly taken into consideration—the novel’s entirety is for the benefit of the writer and his personal needs. This seems to be a major point—Diderot inadvertently argues that writing should not be for the pleasure of the reader, but of the writer. Jacques the Fatalist makes a bold statement on the nature of literature and writing: one should write purely for oneself. It is a statement that many modern writers are forced to constantly be aware of, as the economic focus of literature and writing has corrupted the purity of writing for pleasure.